Learning to Trust Strangers

Dunbar’s number supposes the maximum size of a social network that we can hold and maintain in our heads. The usual estimate is 150. In tribes or villages 150 is about the number of people you need to know to enter a system of trust. In today’s secular urban environment, where most of the people you come across are strangers, establishing trust is more difficult and there is less incentive to be the good guy. Fortunately, we can overcome the limitations of the human mind by information technology.

Uber and Airbnb have shown how reputation and feedback systems can help people to trust strangers. People tend to treat strangers with greater respect when they get a star rating that includes a complementary comment. Imagine if we could extend this trust to all human interaction. You could thumbs-up the friendly bus-driver or the stranger who helped you find the way. Perhaps even the otherwise under-incentivised cop or public servant would also appreciate some recognition?

Who wants to be a bad guy if anyone you meet already knows it? Your reputation goes ahead of you. Against government monopolies of law enforcement and justice, reputation could easily be a stronger, faster, less corrupt and more cost-efficient force for good. It just needs to be done right.

What would a universal reputation system look like? Probably something better than what the creators of Peeple had in mind before giving in to the shitstorm that their “Yelp for People” conjured — although they did get some things right.

We need something better than centrally managed sites or apps that are prone to censorship and do not allow users to easily export and relocate their data. It is essential that a review is not completely removed from the system because someone didn’t like it and pressured the admin. A central point like GitHub is acceptable if the system itself is open-sourced, mathematically verified and decentralised like the Git version control system.

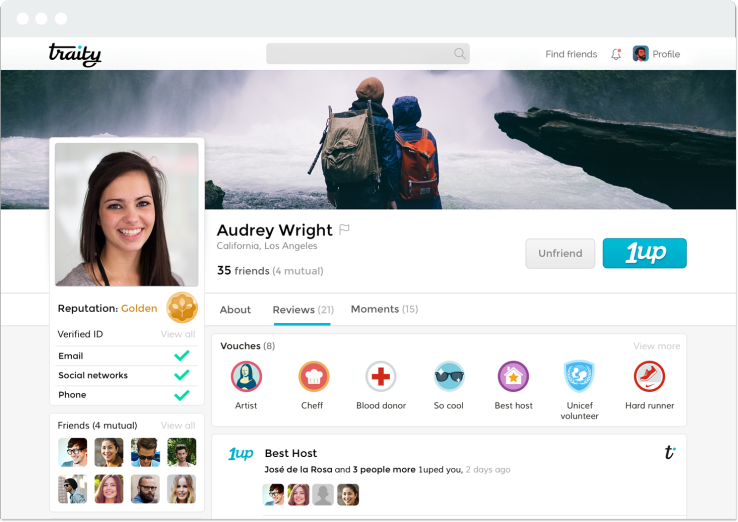

Traity.com, a reputation scorecard site. It is centralized and proprietary, but features a pleasant user interface.

We need something that gives a truthful picture of what the people you’ve interacted with think about you. We do not need the anonymous online trolls, or the restaurant owners who write themselves Yelp reviews on fake accounts. Next to your feedback it should display the reputation and identity verifications of the person who gave the review — and automatically hide the feedback from accounts that have low trust from your extended social network. The same database can be used to filter out social media comments written by fake profiles for propaganda or commercial purposes.

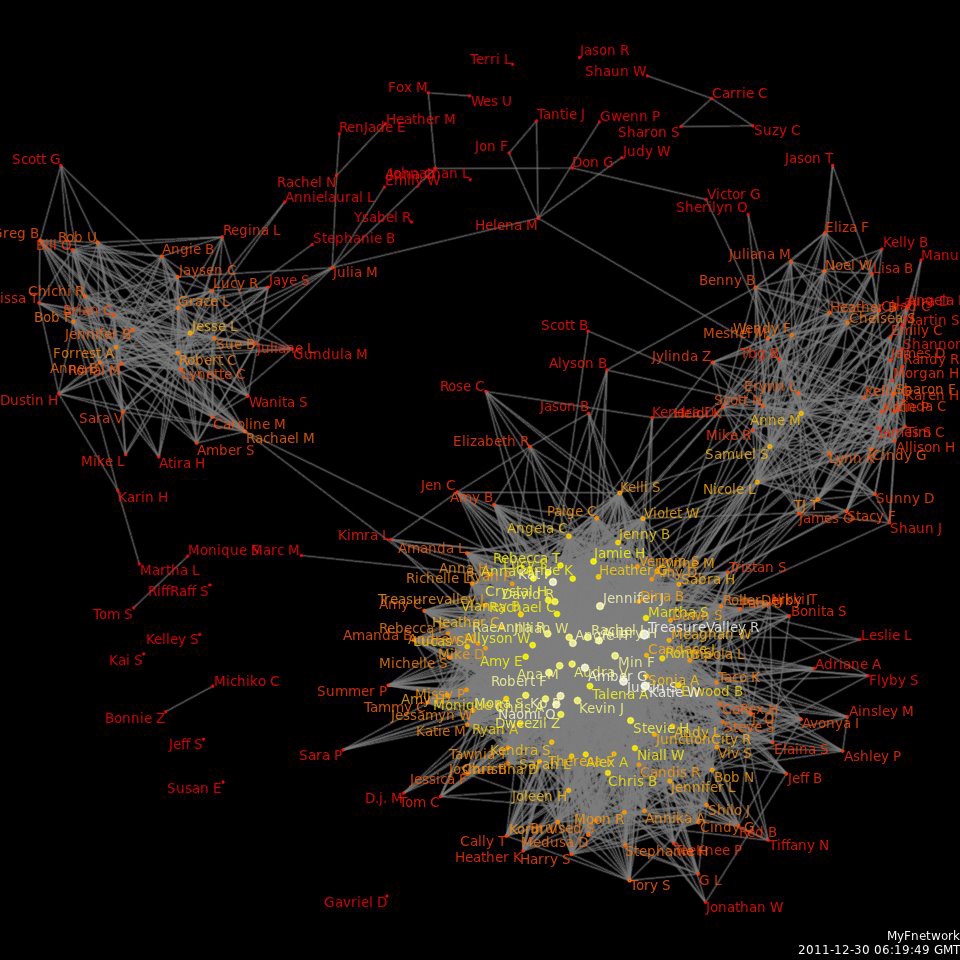

Someone’s reputation is not best represented by a static score that is displayed to everyone. What you see should depend on how your personal web of trust regards them.

Social network visualisation. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

We want mechanics that encourage dispute resolution, apology and compensation instead of endless conflict. Getting rid of a public trail of unresolved disputes should be an incentive in itself, but applications that make third party dispute mediation easier (and profitable) could also be worth experimenting with.

We want reputation to follow the user, even if their email or social media account changes, gets hacked or if they forget their password. The system should bring together the reputation from different sources. On the other hand, feedback needs to be contextually distinguishable — 5 stars on eBay doesn’t mean that you’re a great Airbnb guest, or a good guy in general.

We want to make sure that getting hit by a Twitter lynch mob (case Justine Sacco) doesn’t ruin your life — or at least the system shouldn’t make the current situation any worse. We want a reputation system better than Google search, which doesn’t give an accurate picture of anyone and can be manipulated to one direction or another with search engine optimization.

I have been developing an application called Identifi [2019 EDIT: renamed to Iris] which aims to address these points, besides being a decentralised address book. You can use it to keep your contact details up-to-date, have them verified by peers or a trusted authority and to bring together your trust score from different applications. It stores its data in a distributed fashion on all the computers that run the open source Identi.fi application. It has its bugs and is still very much in-development, but it should point in the right direction with its web-of-trust based content filtering.

Changing the world by yourself is difficult, even if you’re Satoshi Nakamoto. If you think these ideas could make the world a better place, please consider contributing to the Identi.fi codebase [2019 EDIT: Iris] or sharing this post. Let’s shift the decimal points of Dunbar’s number and build a global village society where people can trust each other again.